The chance of accidental nuclear war has been going down

Summary

-

I find there have been ten accidental nuclear incidents in history where I think there was some non-negligble chance that, had things played out differently, there could've been a nuclear exchange.

-

I think the chance of another accidental nuclear incident happening in the next decade (2022-2032) is ~28%. I take a ~5% chance that any given incident will escalate into a nuclear exchange causing at least one fatality[1], putting the chance of an accidental nuclear exchange in the next decade at ~2%.

-

By combining my estimates here with other averages of expert forecasts, I think the overall chance of nuclear exchange (intentional or unintentional) this decade is ~6%.

-

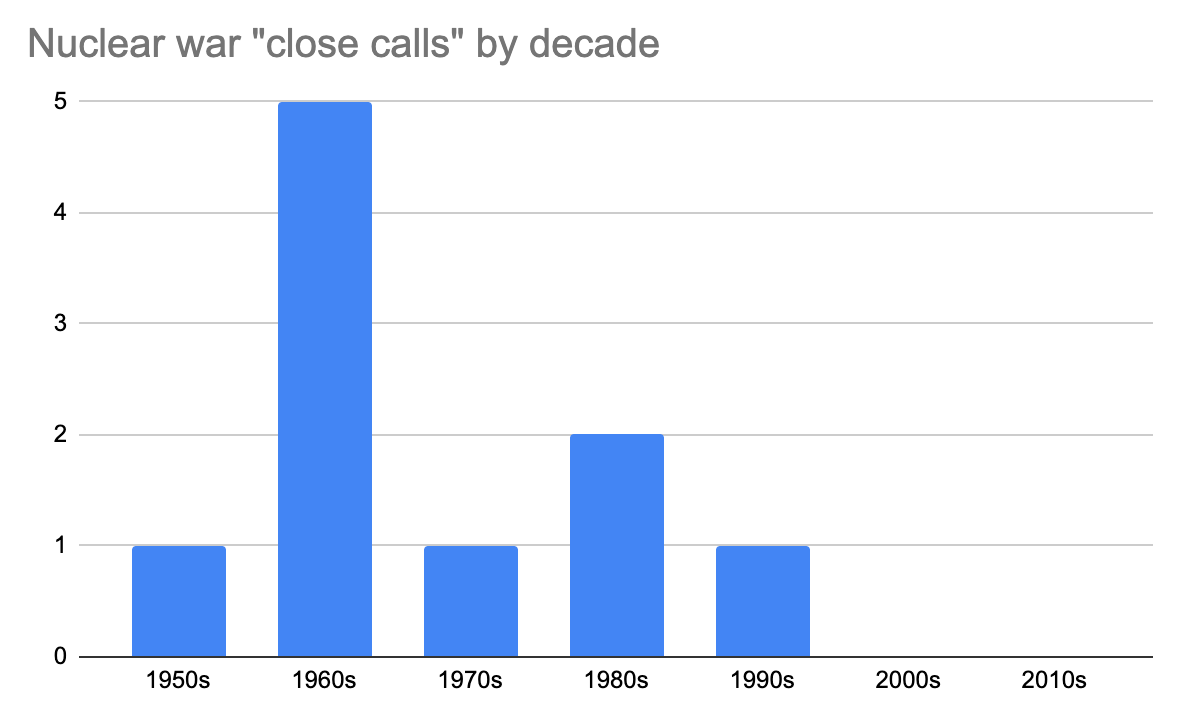

The 1960s represented a high point in the risk of accidental nuclear exchange. The number of incidents has gone down significantly since 1960 and has gone down significantly again after the 1990s, with no such incidents occuring since 1995.

-

Better technology to reduce false positives has likely reduced the risk of accidental nuclear exchange. Many past incidents were the result of computer errors detecting weather or other peaceful events as nuclear launches and these seem less likely to happen now.

-

More time spent between the development of offensive nuclear weapons and now without observing an incident should gradually over time reduce our chance that such an incident will occur in the future, all else being equal. This makes the risk higher in the past than the future, all else being equal.

-

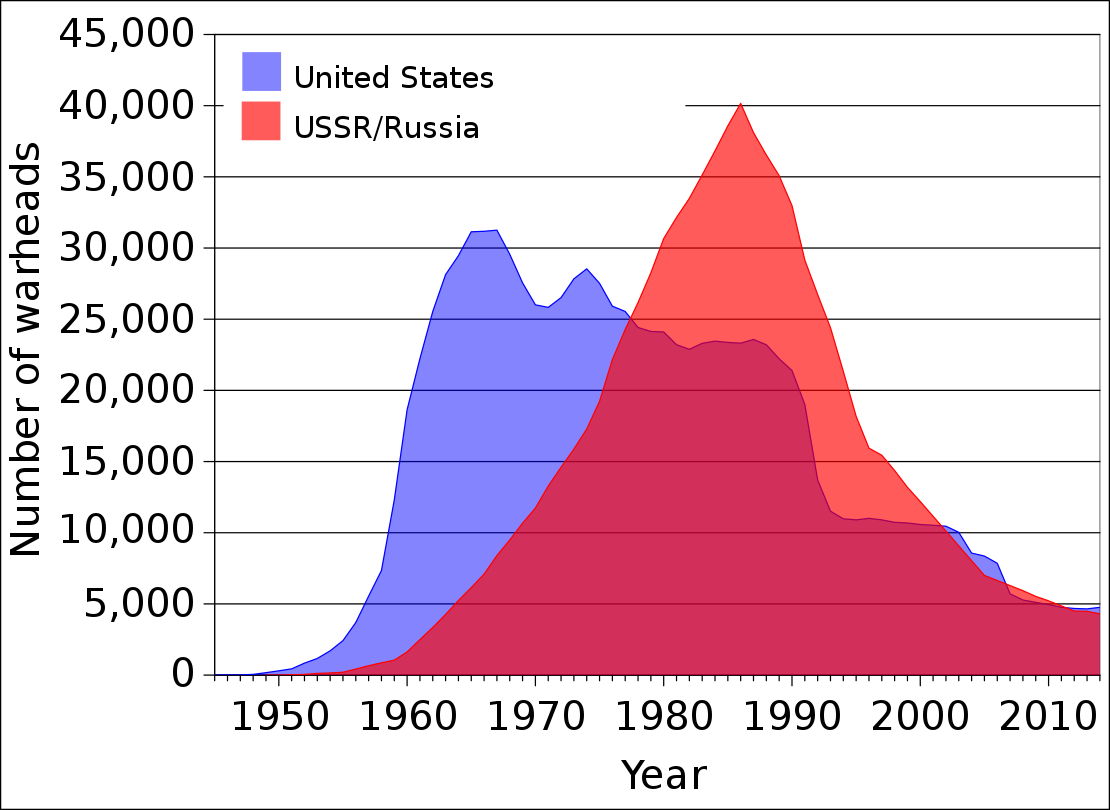

Thanks to international arms control agreements, we have moved from a height of over 63,000 nuclear weapons in the 1980s to under 14,000 nuclear weapons today. This also, all else being equal, reduces risk and shows that progress is possible.

-

We also have much more geopolitical peace since the end of the Cold War and this has likely reduced the chance of accidental nuclear war. But it's possible this era of peace is backsliding given recent tensions with Russia (and also China).

Intro

Hopefully there won't ever be an intentionally started nuclear war, given the logic of mutually assured destruction. But what if a nuclear war starts with the worst accident in history, where a country misinterprets evidence thinking they are under nuclear attack and responds with a second strike before it is too late? And this "second strike" is actually a first strike and gets responded to with a true second strike?

The Data

To analyze, I went through the Wikipedia "list of nuclear close calls"[2] (alarming that there are enough of them to make a list) and tried to filter to only the situations where there was a chance had things been misinterpreted a bit more and gone a different way, there could've been a total nuclear war resulting in massive amounts of death (though likely not complete human extinction).

From this, I got ten such events[3] in eight different years. Seven of these events involve computer errors mistaking innocent things for incoming nuclear weapons and three of which involve misinterpreting enemy actions as signaling potential nuclear intention.

For one example of these incidents - in 1960 October 5, there was a moonrise over Norway that US radar equipment in Greenland somehow mistakenly interpreted as a large-scale Soviet missile launch. Upon receiving the report of this attack, the US went on high alert. However, the attack was doubted because of Nikita Khrushchev was present in New York City as head of the USSR's United Nations delegation. What may have happened had this moonrise incident occured when Nikita Khrushchev was back home?

Charting this by decade shows a large spike of these nuclear incidents occured in the 1960s when the Cold War was at its most tense, and has then apparently subsided, with there being only one such incident after the fall of the Soviet Union:

This data suggests that the risk of an accidental nuclear war has gone down a lot since the 1960s and down even more since the end of the 20th century.

I think there are three good explanations for this: (a) technology has generally increased and we can now better discern between a moonrise and an incoming missile; (b) our understanding of false positives for nuclear threats has increased and we've invested a lot more in being able to communicate about possible accidents; and (c) there has been very minimal conflict between nuclear superpowers post-Cold War.

Any reason to think chances haven't gone down?

Perhaps there are close calls we haven't heard of because they haven't been declassified yet? But this seems unlikely to explain the down tick because:

-

Looking at the timing between these events and when they were disclosed, it appears to take a little over 15 years

-

There has been a strong drop off just between the 1960s and the 1970s/1980s, a period for which there has already been a lot of declassification

It's possible that the chance of cyberwarfare has caused the risk of an accidenal launch to go up (e.g., someone hacks a missile into launching), but I'm skeptical that this will be a major risk factor because I imagine cyberdefense against this will be pretty good and there'd be no real motivation for cyberattacks to lead to actual nuclear launches as opposed to detonations within the silos.

One factor I do think has increased the risk is Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine - as well as general increases in geopolitical tension with China in the 21st century. Both of these trends threaten to undermine the post-Cold War peace we've had been between nuclear powers.

So what is the chance of accidental nuclear war?

Interpreting ten datapoints scattered non-randomly over eight years is more of an art than a science, which makes it hard to figure out what to do to project the risk going forward.

A somewhat complex method is to fit sort of autoregressive Poisson model with time trend. A model like this does think, based on the observed data, that nuclear incidents are decreasing with time and thinks there is an 18% chance of another nuclear incident sometime next decade (2022-2032)[4].

Another approach is to rely on rule of succession but (a) ignoring the 1960s and (b) fitting mostly to the "2000-2020" (relative peace) trend and only somewhat to the "1970-2000" (Cold War) trend due to renewed conflict with Russia (and tensions with China). Such a model suggests 43% chance of another incident over the next decade[5].

It's not super clear which approach is best and it just really goes to show you can have a wide variety of approaches to extrapolation when you only have ten datapoints. Perhaps lets take the geometric mean of both approaches, and conclude a 28% chance of an accidental nuclear incident within the next decade.

Will a nuclear incident lead to a nuclear exchange?

Of course, even if we have a nuclear incident, this doesn't mean we would get a nuclear exchange. Indeed, the ten past incidents have not resulted in this so far. What is the chance of the next one?

If we take rule of succession with a 10% naive prior and update based on surviving ten accidents so far, the chance of the next incident resulting in a nuclear exchange is (1-(10+10)/(10+11)) = 5%.

Combining this estimate with the previous one, I find a ~2% chance of there being an accidental nuclear exchange sometime in the next decade.

What is the chance of overall nuclear war?

Current aggregated expert views which put the total probability of nuclear war (accidental + intentional) is ~9% per decade[6]. My estimate of ~2% per decade above does not include intentional nuclear war, but my guess is that intentional nuclear war contributes another ~2% at most, making my total estimate of nuclear war in the next decade to be ~4%, which shades more optimistic than the experts. Perhaps given these views I'd update my prediction to be ~6%.

It's also important to be clear what we're talking about. A nuclear exchange doesn't actually imply a full nuclear war with 100s of nukes - I think it's only ~60% likely an exchange would escalate into a big war. And even such a war doesn't necessarily mean human extinction. For more, I'd recommend reading work by Luisa Rodriguez, a former colleague of mine, on "How many people would be killed as a direct result of a US-Russia nuclear exchange?", "How bad would nuclear winter caused by a US-Russia nuclear exchange be?", and "What is the likelihood that civilizational collapse would directly lead to human extinction (within decades)?".

Are we at the "highest risk of nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis"?

Some (see here and here) have argued that, given current geopolitical tensions with Russia, we are presently at the "highest risk of nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis".

This seems hard to reason about statistically. We know for certain that there wasn't any nuclear war between the Cuban Missile Crisis and now, so by definition any point of time with any non-zero risk would be the "highest risk of nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis".

On the other hand, these decades of no risk have given us significantly more information to decrease our likelihood of nuclear risk. If I had been writing this blog post sitting in 1980, having observed seven accidental nuclear incidents in just the past thirty years, I would conclude the next decade would have a 93% chance of having at least one incident (indeed it did have two). I would also have somewhat less evidence of the likelihood that such an incident wouldn't actually result in an exchange (concluding 6% instead of 5%), making the total ex ante likelihood of accidental nuclear war as of 1980 somewhat like ~6% instead of the ~2% as of 2022. So it must've been quite scary to live through the Cold War!

So perhaps it is meant to refer not to actual risk calculations, but some more vaguer sense of geopolitical tensions? But even this falls flat - the 1980s had the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and then Reagan increasing military spending and vowing to "confront the Soviets everywhere". And Soviet nuclear stockpiles were at an all time high, with total stockpiles more than 6x larger than they are today.

So I'd suggest that we really are not at the "highest risk of nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis", at least not yet.

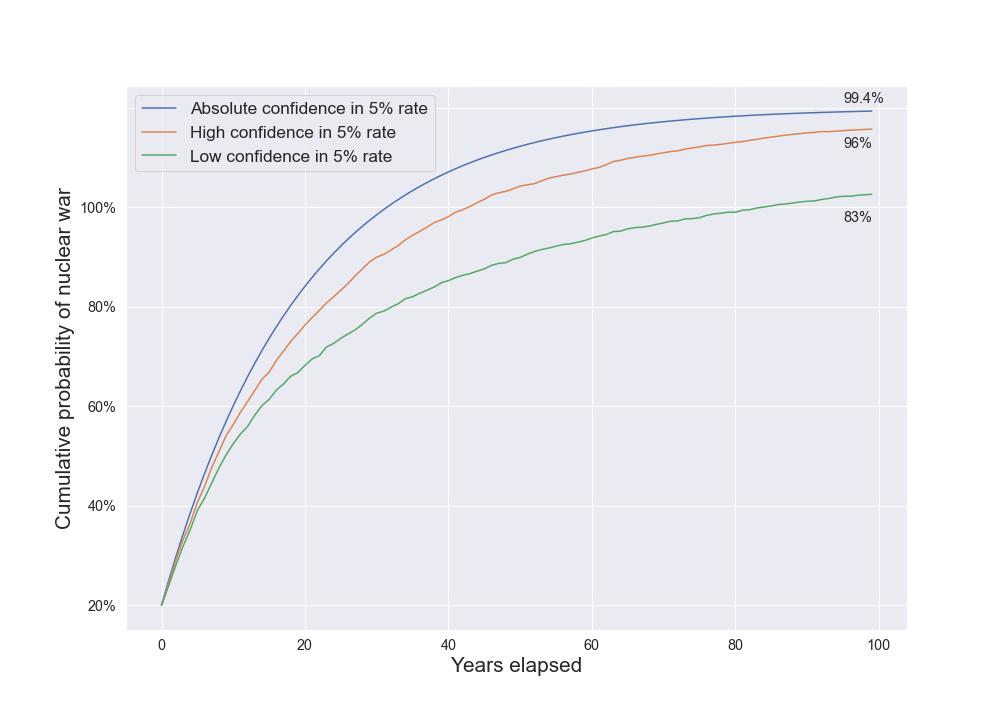

And keep in mind that the longer we go without nuclear war, the more evidence we have that nuclear war is less likely. This matters a lot for projecting nuclear war risk into longer time horizons, a point that David Johnson makes in "A nuclear war forecast is not a coin flip":

The point being here that each year is not independent and the longer we observe no nuclear war over time, the more we need to deviate from our prior. (Though we may encounter other evidence that causes us to shift from our prior in a different direction.)

So hopefully the world will keep appearing more and more safe from nukes!

I use "nuclear exchange" and "nuclear war" here exhcangably but in all cases I mean to predict "two different actors each launch at least one nuclear weapon with the exchange causing at least one fatality" - this could involve something much short of war or could involve a total war with billions of deaths. ↩︎

I also looked through Baum, de Neufville, and Barret, 2018 "A Model for the Probability of Nuclear War", Future of Life Institute's "Accidental Nuclear War: A Timeline of Close Calls", and Nuclear Threat Initiative's "Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons" for any incidens not in Wikipedia's list. ↩︎

The 1956 November 5 Suez Crisis incident, the 1960 October 5 Norway moonrise incident, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 October 28 "Missiles over Georgia", the 1965 power outage, the 1967 coronal mass ejection, 1979 November 9 NORAD computer errors, the 1983 Soviet nuclear false alarm incident with the now famous Stanislav Petrov, November 1983 Able Archer 83, and the 1995 January Norwegian rocket incident. While something like the 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash was scary and could've been quite disastrous, it wasn't an incident that would've resulted in nuclear war. ↩︎

Thanks to Nik Vetr for making this model for me and explaining it to me. ↩︎

The "1970-2000" period suggests a

(4+1)/(40+2) = ~12%chance of a nuclear incident per year, or a1-((1-0.12)^10) = ~72%chance of a nuclear incident within a decade. The "2000-2020" period suggests a(0+1)/(20+2) = ~5%chance of a nuclear incident per year, or a1-((1-0.05)^10) = ~37%chance of a nuclear incident within a decade. If we take a weighted average that is one part "1970-2000" and five parts "2000-2020" we get(1/6)*0.72 + (5/6)*0.37 = ~43%chance of a nuclear incident this decade. ↩︎See also "Samotsvety Nuclear Risk Forecasts — March 2022" for a post-"Russian invasion" take which also suggests a rate of ~9% per decade. ↩︎